Objectification can be a tricky concept to explain to someone who has never experienced it. I’ve had multiple conversations with men who have said, “I would LOVE to be objectified by a woman,” without realizing how that response itself blatantly denies a reality other than theirs.

The textbook definition, “the act of treating a person as an object” feels woefully inadequate. What does that even mean? Objects have no feelings? Objects are valued for their utility? Objects are meant to be still and look nice?

To be objectified is to feel that your body, your looks, and your attention are currency. That, socially, your value lies in being seen and not heard, and that when others seek to “win you over” it is to feed their own egos. It’s an illusion of power and a rejection of depth. I am deeply aware of the effects of objectification on my body and my spirit, and yet I often struggle to describe them. They are both obvious and sneaky, like a sudden slap across the face that leaves you wondering why your cheek is burning.

The problem with objectification of the feminine is its pervasiveness. It seeps into our subconscious in ways we barely recognize, and even good people objectify others without meaning harm, because they’ve been taught that garnering the attention of attractive females raises their status.

Objectification often occurs in the context of sexual desire. Desire can be a fascination with another’s needs, wants, and ideas. But when focused only on the outcome for the one desiring, when one’s desire becomes more urgent than the subjective well-being of its object, it is oppressive.

The difference is agency. A subject is sexual, while an object is sexy. A woman who expresses her sexuality for her own sake is often shamed. Female pleasure without the male gaze is still taboo. But a sexy woman who exists to inspire fantasy is an icon. She creates desire for others without expressing her own.

Conscientious consent is key to countering the subconscious forces of objectification. In the 90’s, we were taught simply, “No means no,” but consent is much more complex than a catchphrase. It is based on equal power, on making space for a no and understanding that a yes must be freely given without coercion and is reversible. This is critical, as many women are conditioned to be people pleasers and, for them, vocalizing a “no” feels challenging and shameful.

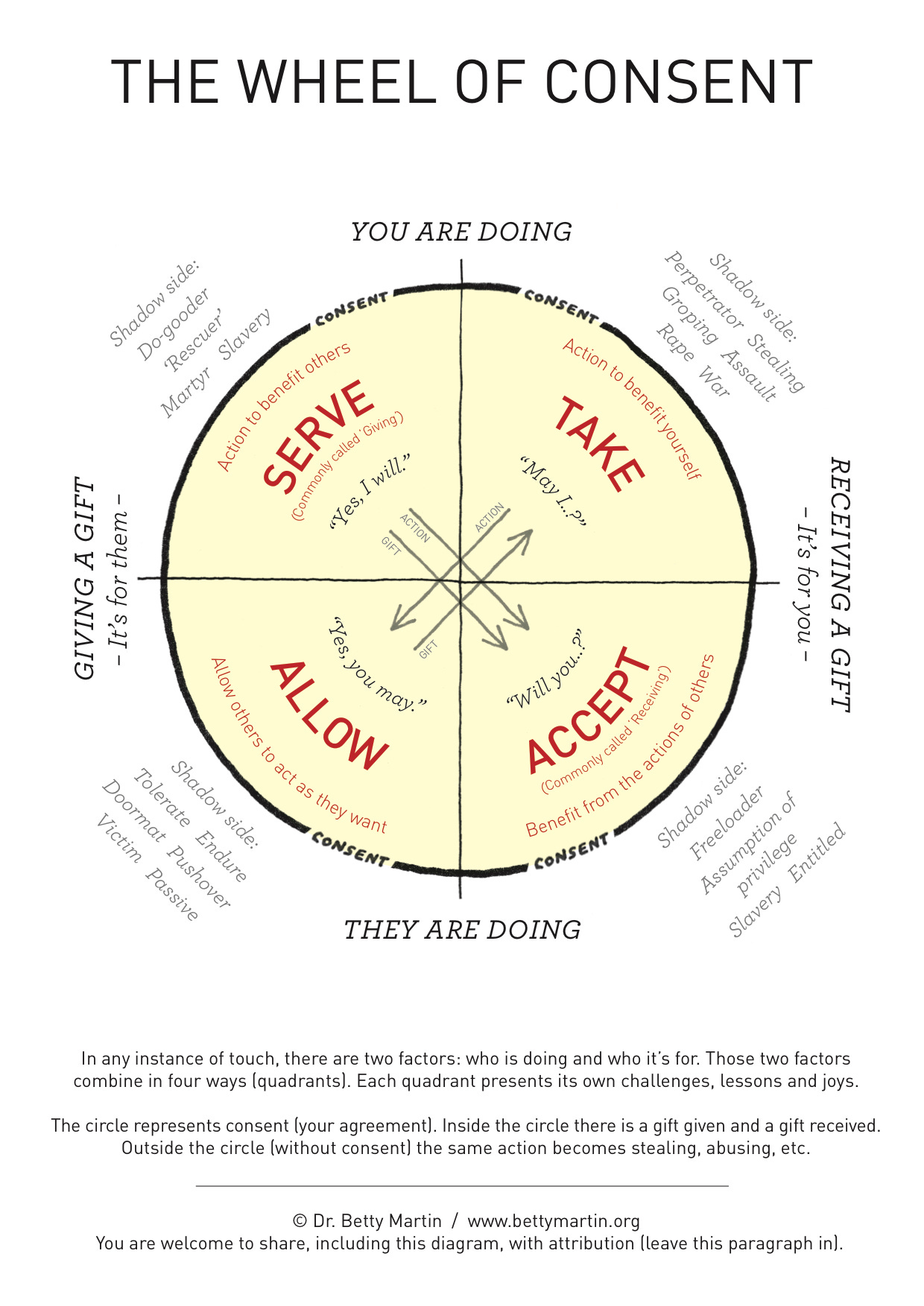

Beyond yes and no, consent is quite nuanced. As a subject, we can serve or take. As an object, we can allow or accept. A critical tool for bringing these nuances to light is Betty Martin’s Wheel of Consent. She envisions consent as a wheel with four quadrants:

She also promotes a game that can illustrate these concepts. Each of the four rounds of the game allows you to explore a different role with a partner. Either you are doing, or they are doing – and the action is either for you or for them. Those two factors combine in four ways:

1. TAKE: You are doing and it’s for you. Ask your partner what their limits are, take time to notice what part of them you’d like to feel, ask May I…? Use your hands to feel, to take in, moving slowly. Remind yourself that this is for you. Say thank you.

2. SERVE: You are

doing and it’s for them. Ask what your partner wants, decide if you are willing and able to do it. If so, do it. Say you’re welcome.

3. ACCEPT: They are doing and it’s for you. Put yourself first and notice what you would like – take your time. Ask as directly and specifically as you can. Stop trying to “give” your giver a good experience. That’s their job. Change your mind anytime and ask for something different. Say thank you!

4. ALLOW: They are doing and it’s for them. Consider your limits and ask yourself, is this a gift I can give with my full heart? Wait for an inner yes. If you are hesitant, you need more info, it’s a no, or you need to set a limit. Say you’re welcome!

Bringing awareness to these subtle differences is an effective way to combat objectification and differentiate power from pleasure. Many of us think we are givers when we do things for others, but often we give to feel better about ourselves, not because the receiver wants what we’re offering.

Post #metoo movement, a lot of people feel confused about how to approach women when it seems like the rules of chivalry have been rewritten. A word of advice? Treat people as subjects, not objects, and grow aware of when you are taking and they are allowing, instead of serving and accepting. We can each be the subject of our own story and rewrite the rules.

Super powerful Rebecca!

I look forward to playing in this.

Thank you!!!